President Trump issued an executive order on Thursday that calls for the internal dismantling of the Education Department, an unprecedented opening salvo in the Trump administration’s effort to relinquish the federal government’s oversight of education to the states.

The order directs Education Secretary Linda McMahon to “take all necessary steps to facilitate the closure of the Education Department” within the “the maximum extent appropriate and permitted by law.”

“The experiment of controlling American education through Federal programs and dollars — and the unaccountable bureaucrats those programs and dollars support — has failed our children, our teachers, and our families,” the order reads.

No president in American history has attempted to shutter a federal agency through an executive order. The Education Department was established in 1979 by an act of Congress, and any effort to close it would require approval from federal lawmakers, many of whom represent districts with schools that rely on funding from the department.

The order appears to conflict with other directives that Trump has signed leveraging the Education Department to pressure schools into altering their curricula, including those that seek to promote a “patriotic” education and restrict discussions on racism and gender.

The directive follows a campaign promise to close a department that the president has portrayed as a purveyor of progressive ideologies. Last month, Trump told reporters that the Education Department was “a big con job” and that “I’d like to close it immediately.”

“We will move everything back to the states, where it belongs,” Trump said in a campaign speech in June. “They can individualize education and do it with the love for their children.”

But the order likely stops short of completely shutting the department. “When it comes to student loans and Pell Grants, those will still be run out of the Department of Education,” Karoline Leavitt, the White House press secretary, said on Thursday. “The great responsibility of educating our nation’s students will return to the states.”

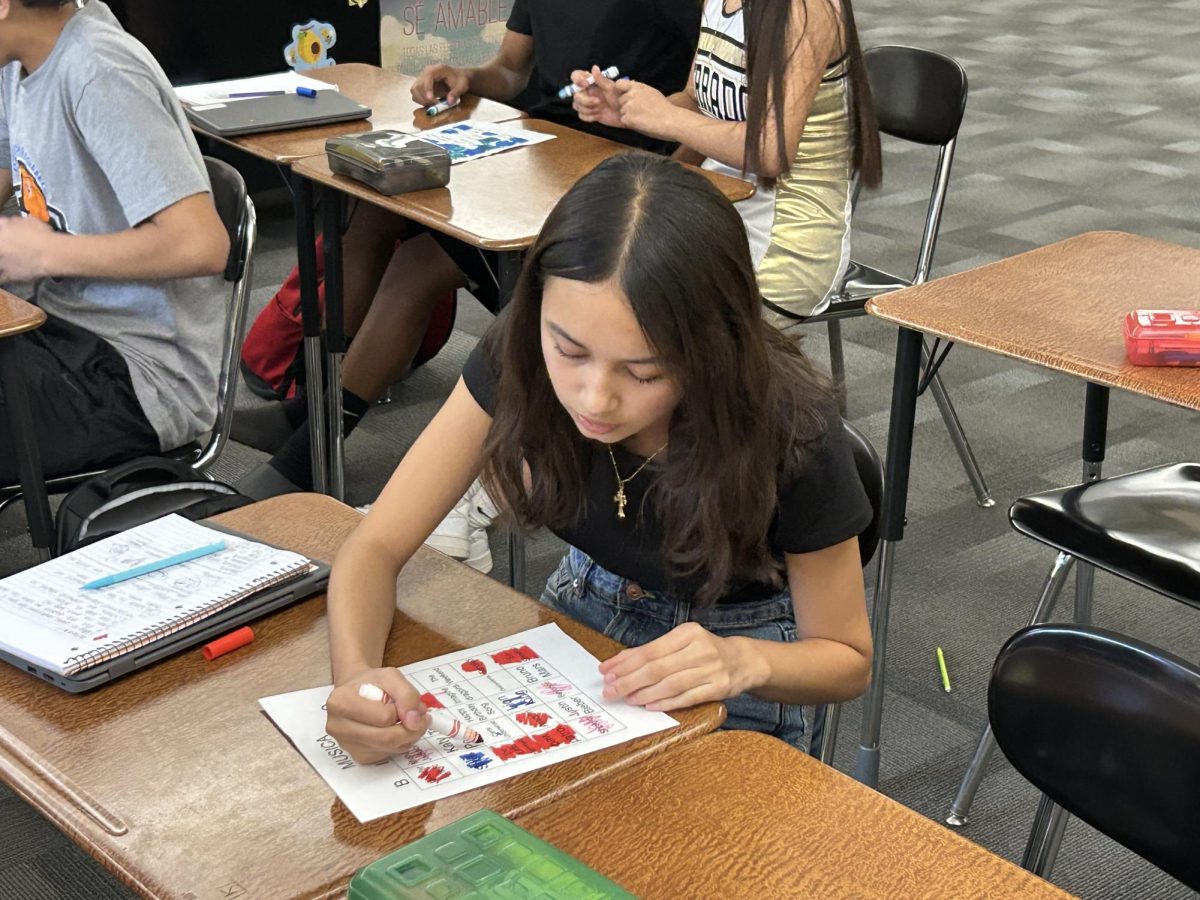

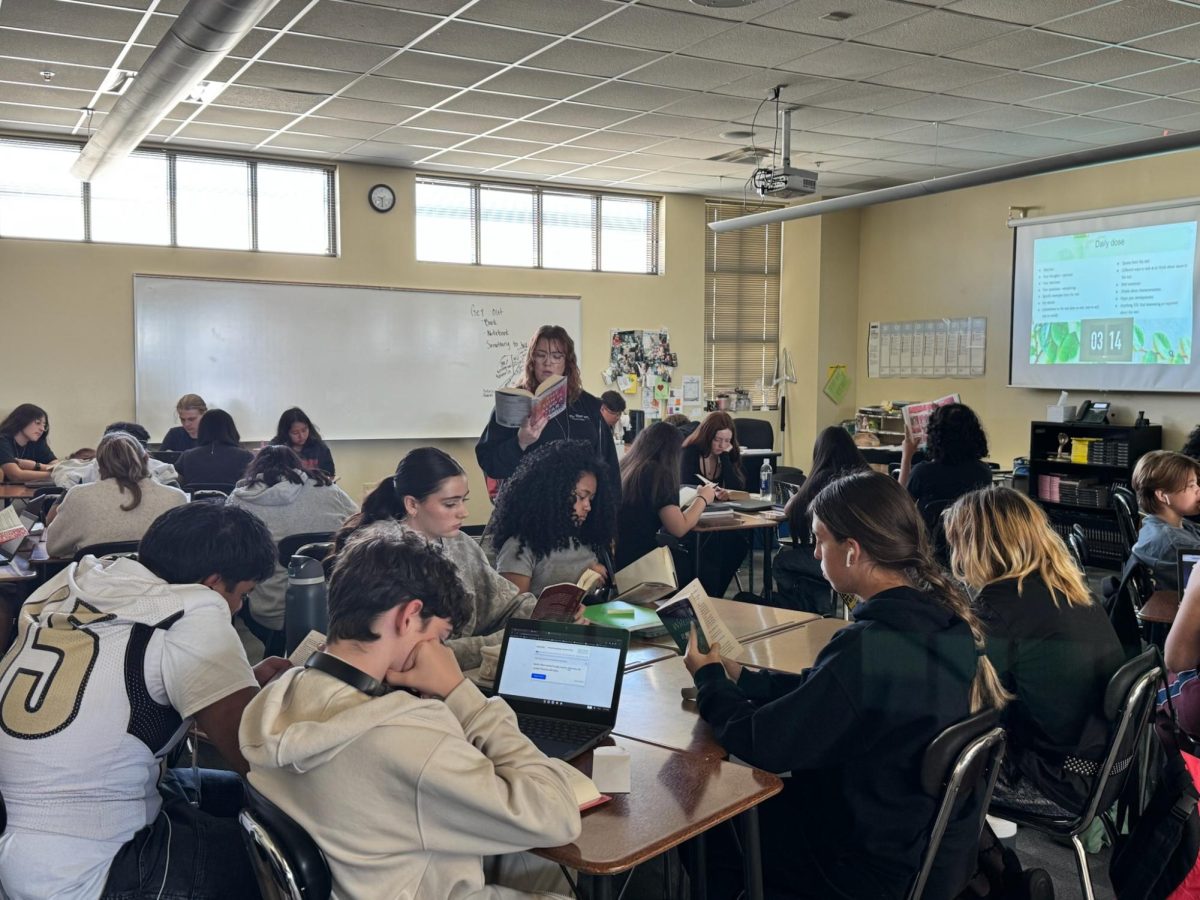

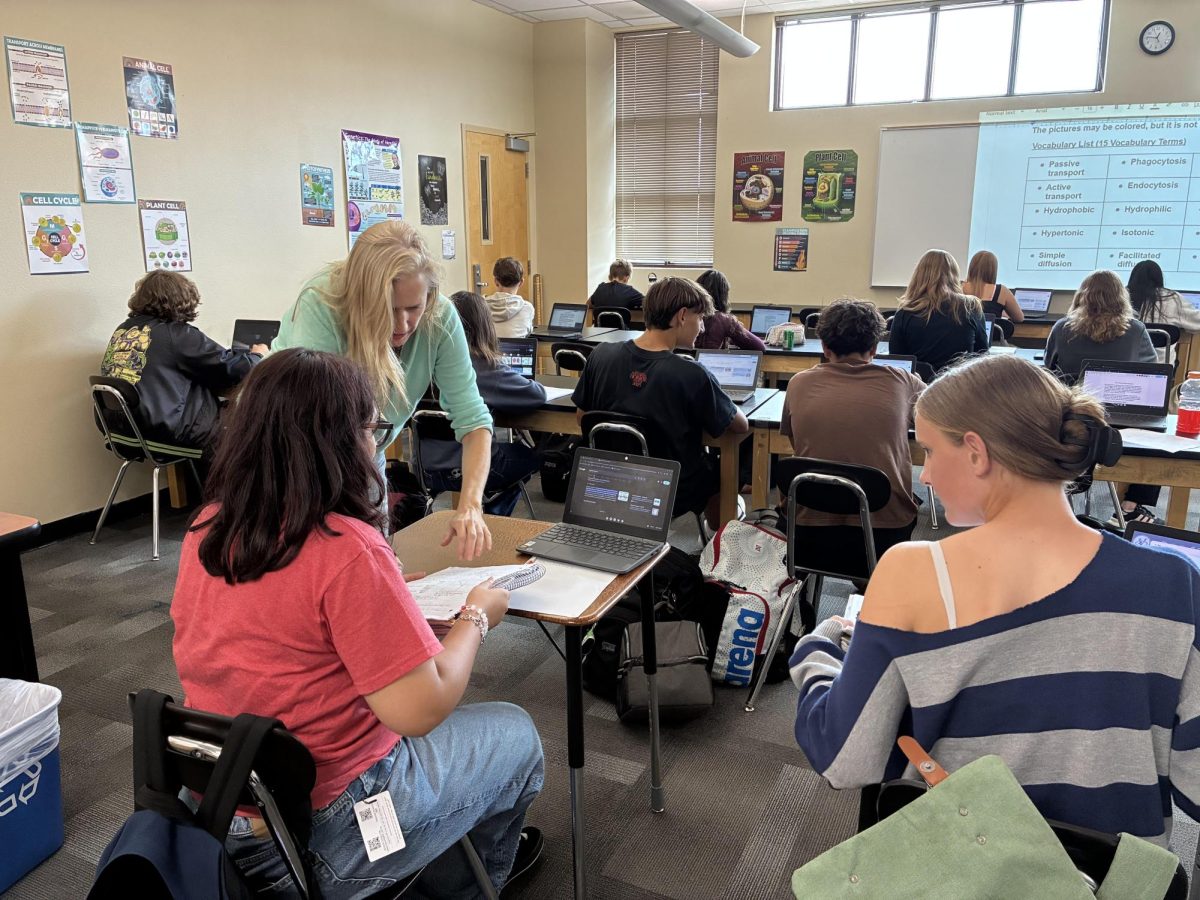

Last year, Agua Fria Union High School District received $12.5 million from the Education Department, representing 11 percent of the district’s total revenue, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. But any reduction in funding could prove detrimental.

Trump previously signed an executive order forcing the Education Department to modify the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program, which forgives a portion of student loan debt for workers in the public sector. Speaking from the Oval Office, he alleged that qualifying nonprofit organizations may be “engaging in illegal, or what we would consider to be improper activities.”

Last month, Trump’s advisers began discussing an executive order that would move to restrict the department’s authority without the involvement of the secretary of education, and The Wall Street Journal reported earlier this month that Trump was set to sign the order as soon as March 6. But hours later, Leavitt said in a social media post that the president would not sign any order relating to the Education Department that day.

The Education Department began laying off roughly 2,200 employees last Tuesday after workers at the department were offered buyouts last month. The job cuts, which amount to about half of the agency’s work force, came after the department moved to temporarily close its offices, citing “security reasons.”

The deep cuts could make it more difficult to provide disability assistance and evaluate math and reading performance across the country as reading skills reach record lows. A third of eighth graders are at a “below basic” reading level, according to last year’s National Assessment of Educational Progress.

At her Senate confirmation hearing earlier this month, McMahon outlined a plan to significantly diminish the responsibilities of the Education Department and delegate some of its functions to other agencies. But she stopped short of echoing calls to eliminate the department completely or reduce federal funding for schools in an effort to assuage hesitant senators.

“I’m really all for the president’s mission, which is to return education to the states,” McMahon said. “I believe, as he does, that the best education is closest to the child.”

McMahon’s first act as education secretary, shortly after she was sworn in last week, was to instruct the department’s staff to prepare for its “final mission.” In her email, she detailed a “disruption” to the nation’s education system with a “profound impact” for students, teachers, and school administrators.

“My vision is aligned with the President’s: to send education back to the states and empower all parents to choose an excellent education for their children,” she wrote. “We must start thinking about our final mission at the department as an overhaul — a last chance to restore the culture of liberty and excellence that made American education great.”

In an interview on “Fox & Friends” earlier this month, McMahon gave a defiant no when asked whether the United States “needs” the agency she leads. But McMahon offered no details on timing or how she will implement the executive order.

“Hopefully, you won’t be there too long,” Trump said to McMahon in the East Room of the White House before signing the order. “We’re going to find something else for you.”

The order is all but certain to incite legal challenges. “Any attempt by the Trump administration or Congress to gut these programs would be a grave mistake, and we will fight them tooth and nail,” Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers, said in a statement.